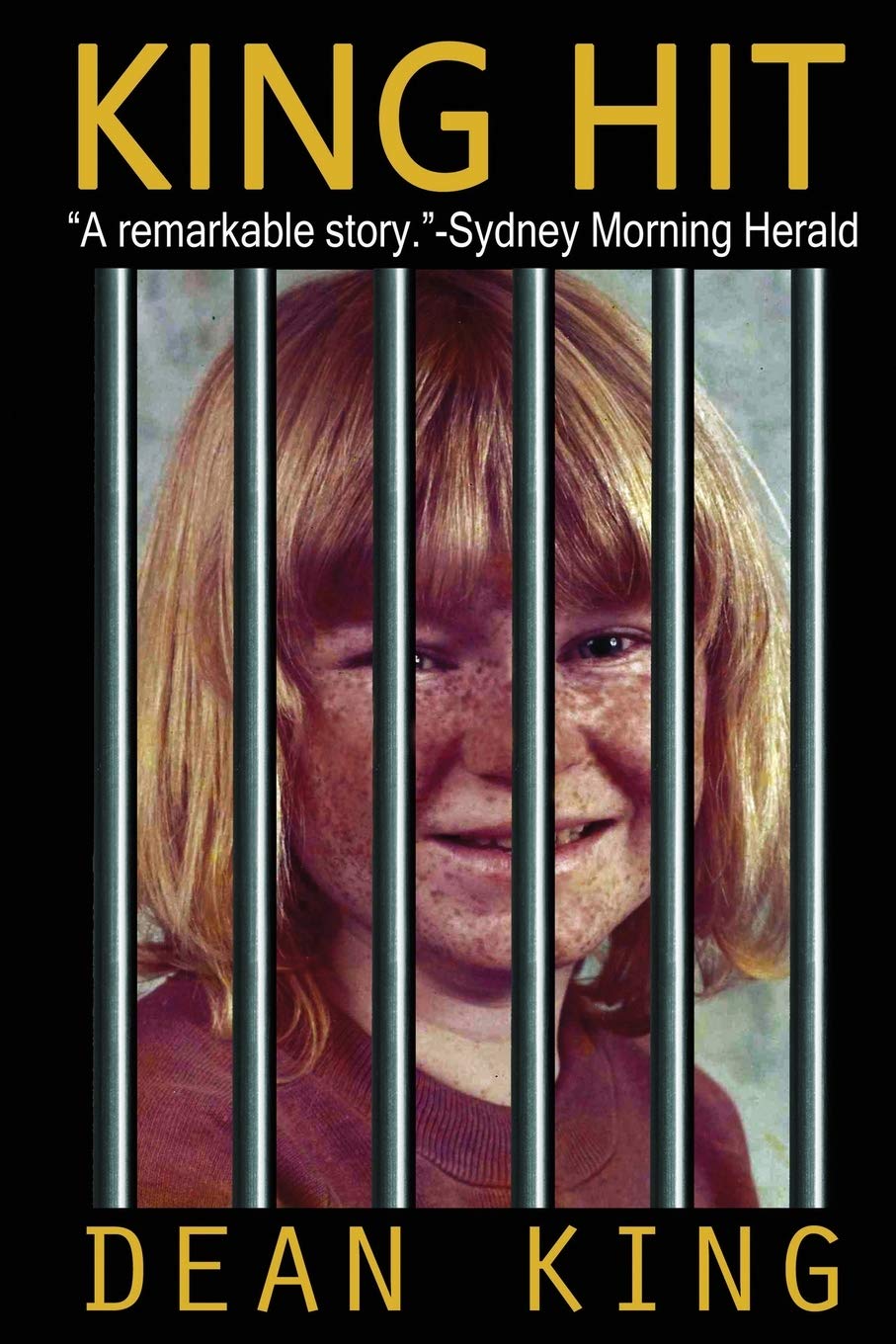

Excerpts From The Book

KING HIT - Further Book Excerpt

screw to open my cell door, I was singing my usual sad song—Eric Carmen’s ‘All

by Myself’ and feeling absolutely and miserably sorry for myself. In fact I was so

despondent that it’s a wonder I didn’t just tie a sheet around the bars and hang

myself. A lot of poor bastards did just that because they felt there was no way of

escaping their personal hell. That first morning back in Boggo Road I was more

angry and dejected than I’d ever been, and already hating the start of this term in

prison more than any other time to date.

Eventually, I was called up to the chief’s office. He told me that some

detectives would be arriving shortly to interview me regarding some other matters.

I had no sooner finished my breakfast than I was summoned to the interview

room.

The same two detectives who had arrested me gestured for me to take a seat.

The blond Nazi and the other guy, who was just a little black-haired runt with a

crooked nose and big ears. They read me my rights. ‘Dean, you have the right to

remain silent. Anything you say may be used as evidence in a court of law. Do you

understand that?’

‘Yeah, yeah.’

The blond one, who I’d taken to privately calling ‘Ken’(as in Barbie’s

boyfriend) smirked. ‘You have been a very busy boy on the outside haven’t you,

King?’

‘Nah.’

They ignored my reply, short and sweet as it was. They arrowed straight in,

asking about particular debit card transactions. Someone had been depositing

cheques into false bank accounts, drawing out the money before the stolen cheques

could be processed by the bank. Back then it took three days for a cheque to clear.

I immediately knew what this interview was going to be about. ‘I want to stop this

interview here. I got nuthin to say about any of this.’

The blond one said, ‘So you’re no longer prepared to do a record of

interview?’

‘No, I’m not.’

‘That’s fine, Dean. You don’t have to do a formal record of interview but

have a look at a few of these.’ With that he leant down, picked up his black

briefcase, placed it on the table in front of him, clicked open the locks and

withdrew a large envelope. He lifted the flap and sorted through the enclosed

photographs.

I said nothing—the evidence was indisputable. Grainy black-and-white photos

of me in the banks. He splayed them out in front of me like a pack of cards. He

foraged in his briefcase again, before pulling out deposit slips and cheques, all

dusted for fingerprints. Evidently mine. Next he tossed a couple of statements in

front of me. They were from bank tellers who identified my mugshot among a

series of photos of other young redheaded guys aligned together on sheets of paper.

My photo had been circled in red with a signature beside it on every page. Every

single teller had identified me. I looked pretty good in that particular photo—I

wasn’t that ugly after all, I thought for a moment.

In my best interests I decided to cooperate. ‘Okay, I’ll do the record of

interview.’ I confessed to all the transactions. I was so very tired and just wanted to

clear the slate and get it all over and done with.

Those illegal transactions had netted me over $100,000 in eight months, most

of it spent on heroin. Time goes fast when you’re having fun. I was charged with

more than one hundred offences—stealing and misrepresentation, fraud, false

pretences, more car thefts and a number of other charges—all of which I guessed

would keep me in jail for the next five or six years.

* * *

After the interview I was escorted into a yard in the old part of Boggo Road.

‘Hey Blue!’

I turned. Right there was Buffalo—the inmate who’d handed me the cricket

bat when I was in the brawl with Texas Bob.

‘What have they pinched you for this time, Blue?’

‘Plenty.’

‘Well, it’s good to hear you’ve been working hard.’

‘Yeah.’ I tried to inject some enthusiasm into my voice. It evidently didn’t cut

the mustard because Buffalo said: ‘Cheer up, Bluey. We’re having a forget-me-

night tonight.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Bombing out big time. We gather all sorts of pills from prisoners who’ve

been prescribed medication.’

I didn’t say anything.

My lack of enthusiasm made Buffalo pause for a moment. ‘Looks like you’re

feeling sorry for yourself Blue. It won’t help ya.’

‘Yeah,’ I sighed. ‘I know, mate.’

Buffalo slung a beefy arm round my shoulder. ‘You’ll hang in Blue, this’ll pass.

Tonight will fix you mate. Now you leave it to me; I got a screw in tow who’ll get

you transferred into our wing.’

That afternoon I was informed I would be going into D wing in the old

Number Two jail. Buffalo had come through as usual.

* * *

That night we were all sitting in D wing watching TV with about forty other guys.

I was now hanging out like a dog—those horrible withdrawals again. This wing

was part of the really old jail. It was three levels high and on the ground level there

was a TV and chairs in a room between the cells, which was where we were. The

cells had no power so we would watch TV here until the screws locked us up at

8.30 each night.

At about 6.30pm Buffalo entered. When he reached us, he withdrew from his

jacket pocket a bag of different coloured pills — like a big bag of Smarties. You

couldn’t tell what was what—whether they were for high or low blood pressure,

for diabetes, insomnia, asthma, herpes, depression or whatever other ailments

might be lurking within the inmates.

Buffalo spilled the pills onto a table and divvied them up.

We each took a handful and swallowed them down with a cupful of water. In

a short time we all grew horns. I started feeling better. Soon we had the music

blaring from Buffalo’s ghetto blaster: The Clash, Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten, The

Cure, Madness, and any punk rebellious music that said ‘stick-the-system-up-your-

arse!’ That music really started the party—many of the other crims joined in.

Some of the guys started kicking chairs and yelling and stamping. Rowdy

wasn’t the word for it! By way of explanation, though not an excuse, in that era

there was a lot of tension in the jail due to the violence of the prison officers. For

instance, in the middle of the night they’d randomly choose a crim and bash him,

using batons, pick handles or iron bars. It hadn’t been that long ago that a pack of

guards had also shot a prisoner in the foot—he was nicknamed The Wolf—saying

he’d been trying to break out of his cell. He hadn’t, seeing as this incident occurred

in the middle of the night and he’d been locked up. The story goes, as he relayed to

us later, that he’d refused to kneel at their order. It had been a fabricated excuse to

put a bit of lead in the poor bastard.

Anyway, this particular night, one of the screws, who was known as a basher,

noticed how loud we were becoming in D Wing. His nickname was Tickets, also

known as The Bus Conductor, owing to how he wore his officer’s hat square on his

head like Blakey from the old show ‘On the Buses’. So Tickets fronted up to the

gate leading into our wing and shouted: ‘TURN THE BLOODY MUSIC OFF!’

‘GET FUCKED!’ Buffalo yelled back. ‘Go back to your kennel you mutt!’

Next instant a guy named Dallas, a real good footballer and a good mate of

mine—God bless his cotton socks for he was one of the notorious Aboriginal

deaths in custody a few years later—anyway he now grabbed the fire hose and

turned it on Tickets on the other side of the gate. The powerful jet sent the screw

flying onto his backside and, as he lay gasping on the concrete floor, he reached for

his walkie-talkie.

It was so funny seeing this stupid goose get blasted that the whole wing

erupted. We clapped and cheered, hurled chairs into the big electricity box. Sparks

flew as water from the hose started flooding the floor. It crossed my mind that

electricity and water were not a good mix but I was having way too much fun to do

or say anything. Owing to a pile of plastic chairs which we’d stacked at the

entrance and set them alight, a raging bonfire soon had flames leaping high at the

iron gate, and smoke billowing all the way up the wall to the old iron roof. Because

the walls were painted once a year without any sanding back, there were decades

and decades worth of paint layers. More fuel for the fire. The fire swiftly became a

ravening beast, sucking up oxygen in the wing and the roar and heat were

indescribable. The smoke was so thick and acrid that no prison officer could enter.

Now they had a full-scale riot on their hands.

Meanwhile we had to cover our faces with our T-shirts, coughing, spluttering,

our eyes streaming. We scarpered to the back of the wing where we could breathe

more easily.

Guys who had gone to bed on the 6.30pm bed call were screaming and yelling

from their cells: ‘Open up, let us out!’

Soon there were at least sixty prison officers in full riot gear, armed with batons

and transparent shields, gathered on the grass in front of D Wing. A few screws

aimed a couple of fire hoses through the gate and the bonfire was soon

extinguished. Other officers had armed themselves with pick handles and couples

were wielding iron bars. This was the MEU—Metropolitan Emergency Unit—they

had been called in and they meant business.

On our side, Buffalo took charge. He calmed the prisoners down. ‘C’mon boys,

settle down. Let’s use this as an opportunity to air our grievances.’

We certainly needed better conditions in this old section. It had been built

eighty years ago—it was now 1986—and all these decades later the cells still had

no running water or toilets. We were pretty fed up with having to carry our shit tins

out of our cells to empty them at the back of Four Yard and then back in again.

How we hated those tins but the cockroaches didn’t.

‘Hey Boss!’ screamed Buffalo. But there was so much noise, he had buckleys

of hearing a reply. ‘Shut up the lot of ya!’ Buffalo yelled at the inmates.

They immediately quietened but the atmosphere was still palpably tense. I

knew of the riot that had taken place last year. The screws had come down with all

their might on the prisoners, bashing every single one involved, and some that

weren’t. In turn the crims had arked up big time to their wives, girlfriends, the

press, solicitors—one even took the case to the United Nations. The upshot was

that the Minister nearly got the sack. So now we knew we had some leverage.

Also, now in these years, the prison system was only just stuttering along. Lots of

protests, hunger strikes, riots and it seemed that not a week passed without

something about the condition in prisons being in the national papers.

‘Reynolds?’ The Chief’s voice echoed down from the gate area. ‘Are you the

spokesperson?’

‘Not officially, Boss,’ said Bufflao, ‘but I can tell ya what the boys in here are

pissed off about.’

Some of the crims cheered.

‘Now, we only want better conditions, Boss,’ Buffalocontinued. ‘It ain’t right

that in 1986 we still have to take a dump in a shit can.’

‘Too right’ and ‘You tell him’ rang out along with more cheering.

‘No!’ Buffalo shouted back. ‘But I am telling you what the boys in here are

pissed off about!’

Again there was some cheering.

‘We want out of this section of the jail,’ Buffalo shouted. ‘We want to go over

to the new section with its running water and toilets in their cells. If we have to

stay here, you are going to have a bloodbath on your hands tonight, Boss!’

I’d never seen him so serious. He wasn’t going to back down. Caught up in

the moment I added my twenty cents worth: ‘Yeah!’ I shouted over Buffalo’s left

shoulder. ‘Remember Bathurst 1974.’ These were the biggest jail riots in

Australian history. ‘Yeah!’ I shouted again, really caught up in the high excitement

of it all.

Buffalo winced. ‘Oiy, Blue,’ he said to me softly. ‘Frigging hell, mate, yer

nearly blew me ear off with yeryelling. Let me do the talking, hey?’

‘Yeah,’ I muttered. I had a lot of respect for Buffalo else I wouldn’t have

backed down.

It was the Chief’s turn to shout. ‘That’s impossible Reynolds; we can’t move

the whole wing to the other side now,’ the Chief shouted. ‘It’s nearly midnight.’

‘Well, get fucked then. We’re burrowing in here for as long as it takes!’

‘Hey Buffalo,’ I said. You couldn’t keep me down or quiet for long. ‘Tell

them to sack Tickets while you’re at it.’

‘Wake up to yourself Blue.’ Buffalo elbowed me. ‘One thing at a time.’

‘It could work,’ I whispered back.

‘Boss!’ Buffalo screamed so suddenly I winced. ‘Another condition is that

Tickets has to be sacked!’

The prisoners cheered loudly this time and the chant was taken up of: ‘SACK

TICKETS, SACK TICKETS, SACK TICKETS!’

Buffalo shushed us and when the chant finally died out we heard Tickets, the

old bastard, shout back: ‘Get fucked the lot of you, you low cunts!’

Well, that was the only excuse we needed. We started up again. ‘SACK

TICKETS!’

‘C’mon boys, enough,’ said Buffalo and that was enough to silence us. We all

bowed to his natural authority.

The Chief’s voice rang through the gates once more: ‘Reynolds, we want to

sort this out in a non-confrontational way. We don’t want the same thing to happen

as last year. Now come to your senses. If everyone comes out now no one will get

hurt.’

Yeah right, I thought. Going by past anecdotes, that didn’t sound very likely.

‘Just come out into Three Yard and we’ll clean this wing up.’

I urged Buffalo: ‘Try and get buy-ups weekly instead of monthly.’

Buffalo nodded at me. ‘No,’ he shouted back towards the gate. ‘I got more to

say. What about buy-ups boss. Getting them monthly is a fucken joke and you

know it. We want them weekly!’

There was a long pause. We waited, straining for the Chief’s reply. Finally

after what seemed like an age, the Chief’s voice echoed back. ‘Reynolds, okay, I’ll

work with you on your requests.’

‘Give the cunts nothing!’ we heard Tickets remonstrating with the Chief until

he roared ‘ENOUGH!’ and Tickets fell quiet.

By now we’d approached the gate. We all started smashing the bars again

whether due to Tickets’ words or whether because we were so frustrated, or a

combination of the two, who knows.

‘Settle down!’ Buffalo screamed but this time he couldn’t control us

immediately. Eventually we did quieten and Buffalo was back at the gate taking

control.

‘What are we going to do now?’ I said to Buffalo.

‘Have a smoke and relax. It’s only early.’

The riot squad were still in place on the other side of the bars.

We grabbed what we could: broken chairs, bits of table, shit tins from

cells—we sat in the water on anything we could find. We waited and waited,

choofing away on our White Oxes.

Finally the Superintendent came to the gate and called for Buffalo. ‘Reynolds,

look around you. Cut electricity lines, wet and smashed power boxes. You’ll all be

fried if the electricity is turned on.’

Fuck! He had a point I thought.

The screws had turned the power off when the riot first started. By now we’d

been barricaded in for five hours. The pills had worn off for most of us and we

were dead tired, cold and simply wanted to go to bed. Others were still drifting in

and out of sleep from the illicit meds.

The Chief spoke again: ‘I’ll only talk to you, Reynolds, if you get those other

prisoners down to the back of the wing.’

‘All right, boys,’ said Buffalo. He leapt up on a shit tin to address us like we

were a bunch of union delegates. ‘Let me negotiate with the Super for our weekly

buy-ups and to improve our conditions.’

We agreed and soon Buffalo and the Boss were bargaining through the gate,

negotiating out of our earshot. They were there for about fifteen minutes while we

waited at the back of the wing.

Buffalo returned. ‘Okay boys, listen up. This is what I got us. Buy–ups every

fortnight and, as cells become available on the other side, we will get first

preference.’

It was better than nothing. After consulting with us he shouted back at the

Super: ‘We’re coming out now but I want your assurance that none of the prisoners

will have to run the gauntlet of the screws. If anyone gets touched there’ll be a

fucken square-up.’

‘You have my word, Reynolds,’ shouted the Superintendent.

Buffalo nodded as he looked at us. ‘Okay, boys, you ready?’

I didn’t know about the others but I felt like a lamb being led to the slaughter.

We filed out of the wing, real twitchy, but there was no running the gauntlet

this time. We entered Three Yard in an orderly manner giving the screws the space

and the time to assess the damage.

* * *

In the light of the following day it looked as if the whole wing had been hit by a

bomb. And the stench! The smell of fire and burnt plastic and paint was still

strong. The walls were blackened and blistering all the way up to the roof.

I was summoned to the Chief’s office, with Buffalo. The chief told me I’d be

moved to the other side of the jail to keep me away from trouble. I knew it was

because Buffalo had taken a real shine to me from the first day he’d met me when I

was fighting Texas Bob. I couldn’t have cared less about being moved but their

modus operandi was to divide and rule.

Buffalo was informed that as ringleader, he would be spending the next two

weeks in the cages or the DU—the detention unit.

‘Jeez, that’s a bit harsh, Boss,’ said Buffalo. ‘Especially when I settled them all

down and managed to keep the peace for you guys.’

But the Chief didn’t buy it. ‘Stop speaking shit, Reynolds, you know as well as I

do you’re a big mouth.’

‘FUCK YOU, YOU OLD DOG!’ Buffalo exploded.

‘TAKE HIM AWAY!’ the Chief yelled to his officers.

And Buffalo was dragged off, bellowing until he was out of earshot.

Chapter Sixty Five

I stayed in a locked cell for a couple of hours until later that afternoon I was put on

escort for Woodford where I was placed in solitary for three months. From

Woodford I was taken back to court in Brisbane where I was sentenced to three

years for the chemists’ busts, break and enters, car stealing, and being in

possession of drug paraphernalia. Straight after sentencing I was taken to

Rockhampton via Childers Police Station where we stopped and had a feed of

sangas followed by a walk around the yard.

In Rockhampton—Etna Creek—I was placed in the lock-up for eight months. In

the adjacent cell was the notorious rapist who we knew as The Beast. He was a

little Aboriginal bloke—he’d had to be removed from mainstream due to his sexual

assaults on other prisoners. He told me ghost stories—about how crims had hung

themselves in the cell in which I was now living. He’d heard a few hangings over

the years he’d been in Etna Creek.

I’d say: ‘Shut the fuck up, would ya.’

But he’d giggle and laugh and say: ‘You scared Blue?’

‘Yeah, mate, fucken oath I’m scared of ghosts.’ One of the stories was that

before I arrived the toilet would mysteriously flush in the middle of the night and

how he heard voices: ‘Let me out of here, let me out.’ Those stories gave me the

cold shivers and really scared me.

* * *

After Etna Creek, it was back to Boggo Road. I was spirallingdeeper and deeper

into the prison system. And, two and a halfyears after being charged for the

chemist and shop robberies, my sentence for that was just about to expire. But I

had to wait until the courts sorted out the problems with my other charges—the

hundred or so charges of fraud and false pretenses had been held up due to a

problem about jurisdiction —whether the case should be heard in the Supreme

Court or in the District Court. I was just about to go on remand for all the fraud

charges, and hoping to get out on bail.

One morning I was walking over to the food mess, puzzling over how I could

get out of prison on bail. I wasn’t exactly hopeful, after all there were a lot of

charges. But, undaunted, I sought assistance from a crim who had studied law and

considered himself a regular Ironsides. I could never understand how guys who

were supposedly so smart still finished up in prison.

Anyhow, Ironsides asked to see my criminal history, the record of which I

gave to him the next day. He was shocked when he counted the number of times

I’d failed to honour bail commitments. He looked me straight in the eyes. ’You got

any money mate?’

‘Why?’

‘Because there’s not a court in this land that’s going to let you out on bail

without security based on how many times you’ve failed to appear in court.’

‘Oh,’ I said. I couldn’t think of anything else to say. I must’ve looked very

crestfallen because he said he wanted to think about my case but I could tell he

wasn’t optimistic. If I failed to get bail for these charges I’d probably be waiting on

remand for at least another six months. This would leave me and my case in limbo

for a long time— it had already been three years.

The next day at noon I was on my way to the server for lunch when Ironsides

called me over to the fence. He made it quite clear that as I didn’t have money any

bail application would be unsuccessful. His voice softened: ‘But I’ve got an idea.

Have you considered going to a drug rehabilitation centre?’

‘What?’ I reared back.

He told me that he’d made successful applications for other druggos in the

past. ‘It’s a way of getting you out on bail, Dean, and perhaps changing your life.

The programme is new, only been going a couple of years. It’s run at a centrecalled

Logan House.’

I couldn’t believe it. Was he serious? ‘Those sorts are all dogs. They give

each other up. No way.’ I turned on my heel and stalked off. Anyone who needed

help was weak and that didn’t apply to me. I needed help from no one—it went

totally against the grain of who I thought I was.

I’d previously met people who’d walked out of rehab joints and they’d said

how awful it was having to talk about their lives. People who went to rehab were

weak fuckers. Moreover, one of my best childhood mates, Ken Lavelle, had been

sent to WHOSE (We Help Ourselves) and I reckoned they’d brainwashed him for

sure. They really fucked him up—he stopped using heroin but mostly it was

because we were never the same again—it felt like I’d lost a really good mate. But

he didn’t stay off the stuff. He died from a heroin overdose. God bless.